We descend a full level in a single canto! After the avaricious and the prodigal, the pilgrim and his guide scramble down to the next circle of hell: the wrathful. Or really, the wrathful in two states, a perversion of Leah and Rachel in medieval iconography. This passage is also stocked with naturalistic imagery. The poem is settling into its stride—despite the fact that it’s breaking the walls of the cantos.

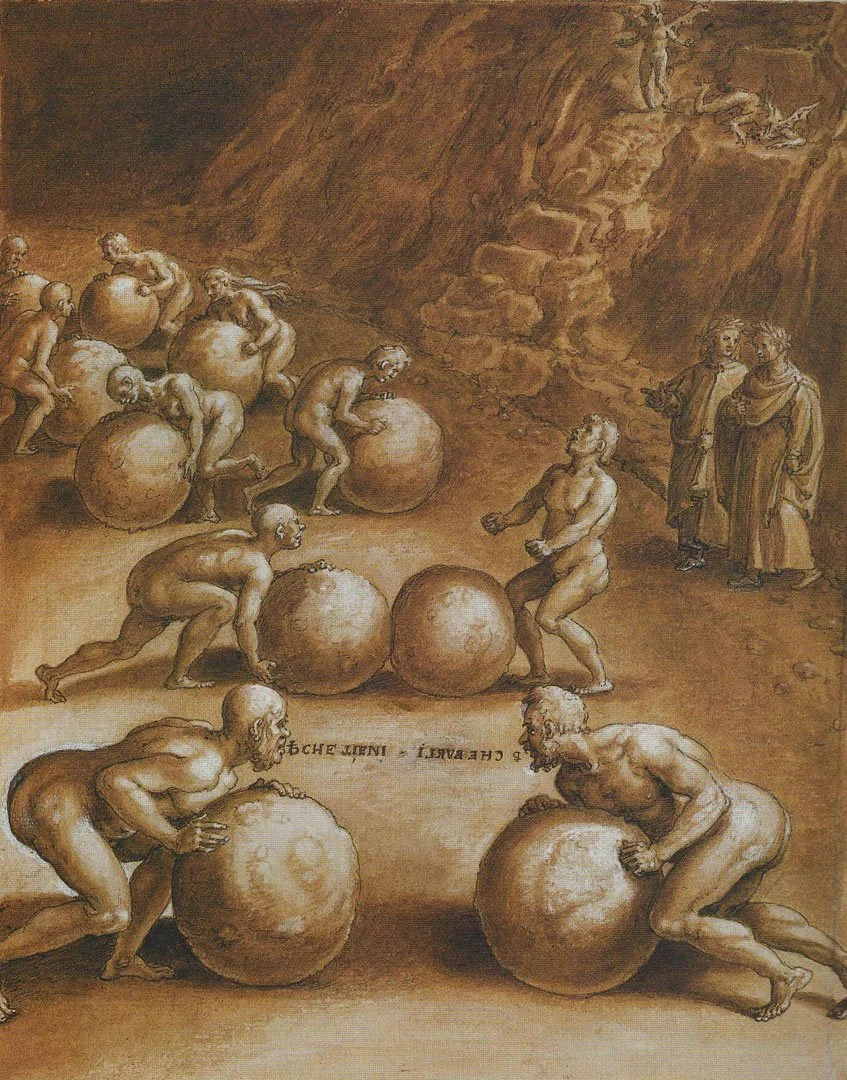

Read MoreAfter we’ve seen the ones who hoard and the ones who spend too much, Virgil steps back and offers a boiler-plate sermon straight out of Boethius’ THE CONSOLATION OF PHILOSOPHY. But maybe that sermon’s not all it’s cracked up to be. Maybe the poet has left us some hints that there’s more afoot here than may first meet the eye.

Read MoreThe clergy, even popes. And avarice. Plus, Aristotle. It’s packed into this dense passage from Canto VII of INFERNO. Packed enough to cause cracks in the poetry. I’ve also got some thoughts on the anti-clerical nature of some passage of COMEDY. And some further thoughts on why the pilgrim, Dante, doesn’t seem to recognize anyone in the fourth circle of hell.

Read MoreThe fourth circle. The great enemy, Plutus. But more questions. Who is this Plutus (or Pluto) at the entrance to the circle? What’s he saying? Why’s he so easily put down? And why does Virgil have such a fine grip on Christian theology? So many questions—with no time to answer them as we’re hoisted up to get a bird’s-eye view of an entire circle of hell for the first time in THE DIVINE COMEDY.

Read MoreAs Ciacco sinks back into the muck and loses his humanity, our pilgrim, Dante, and Virgil walk on, talking about the last judgment, perhaps a pressing subject since Ciacco has just told the future of Florence. Virgil offers his very wrong assessment of the Second Coming, then goes on to call the pilgrim back to Aristotle to figure out how the soul and body interact.

Read MoreOur pilgrim Dante and his guide, Virgil, have heard Ciacco’s first answer about who he is. But our pilgrim is not satisfied among the gluttons. He wants to know more and more, including where certain men have landed in the afterlife. Dante keeps calling Ciacco out on stage. When is enough enough?

Read MoreOur pilgrim Dante walks on top of the filty gluttons until one of them, Ciacco, sits up. He’s the emblematic glutton and our first Florentine. He’s lost to history but he leaves a mark on COMEDY as he fuses gluttony with a second sin and begins a larger discussion of the role of gluttony in civil unrest.

Read MoreAn introductory episode to the sweep of the podcast WALKING WITH DANTE. A bit about how we’ll proceed through The Divine Comedy and a bit about who I am. But mostly, just a deep breath to get you ready for the journey ahead.

Read MoreDante, our pilgrim, wakes up already in the third circle of hell. How did he get there? No clues! But it’s a place with incredibly bad weather and rancid, fetid pools of muck . . . as well as Cerberus, a figure out of THE AENEID, now changed by Dante’s art and maybe even with Virgil’s help.

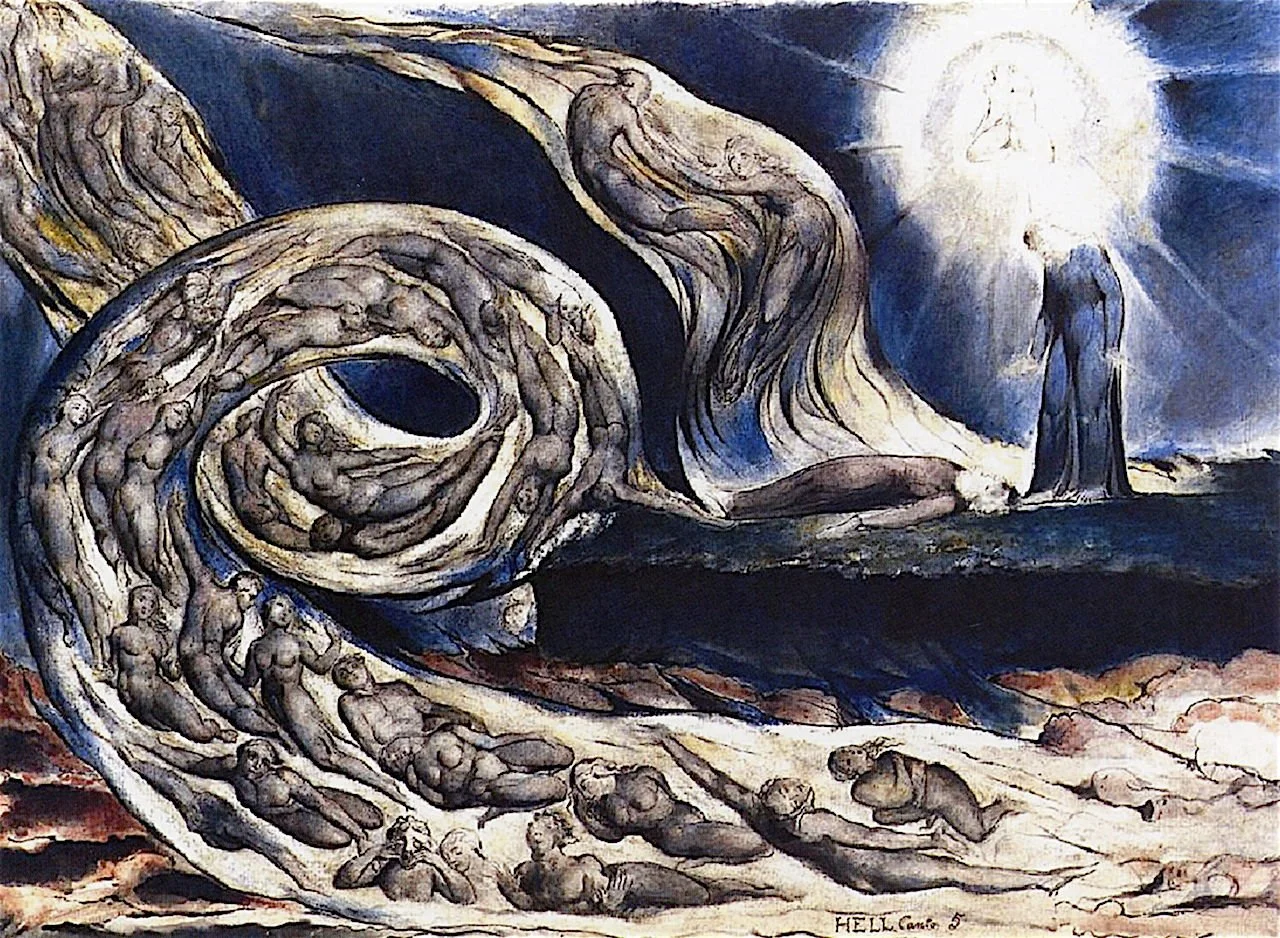

Read MoreLong seen as one of the oiliest sinners, Francesca may be much more: a character who escapes not only the pilgrim, but Dante himself, her creator. Her speech is so great that she escapes the prison of the words the poet has crafted for her, words that ultimately express his unfulfilled desires with Beatrice.

Read MoreIn INFERNO, Canto V, we meet our first great sinner: Francesca (and her lover Paolo). Let’s I’build a case against Francesca, showing her to be the gravest threat yet to our pilgrim as he walks across the known universe. She is an oily, flattering seducer who will do anything to duck the blame she deserves.

Read MoreOur pilgrim, Dante, has asked Virgil who is out on the wind. Virgil answers with a surprising list of the "greats,” moving the timeline from ancient history to contemporary (medieval) romance. Along the way, Virgil does something much subtler: he redefines lust as love. And he may even goad our pilgrim on to do the same.

Read MoreHaving left the judge Minos behind, our pilgrim, Dante, and his guide step up to the winds of lust: a relentless storm that provokes a gorgeous simile as the pilgrim stares into this abyss. The poetry is lush and enticing. And it hides clues for what’s ahead, both in this canto and on down the road in INFERNO.

Read MoreIn this interpolated episode of the podcast WALKING WITH DANTE, I’ll offer a historical overview of the seven deadly sins. Why these sins? And why are there seven? Who decided which sins “count”? And does Dante concur? (No, not in INFERNO!)

Read MoreOur pilgrim, Dante, comes to the second circle of hell and encounters Minos, the sure judge of sin, an epicure of vice. Minos offers a judgment on all the souls before him (but not on those back in Limbo!) and seems to try to shove a wedge between our pilgrim and Virgil, his guide. But Virgil’s got an answer: a tried-and-true spell. Rhetoric works. Sometimes.

Read More