34. Fate And The Cracks In Dante's Poetry: INFERNO, Canto VII, Lines 36 - 66

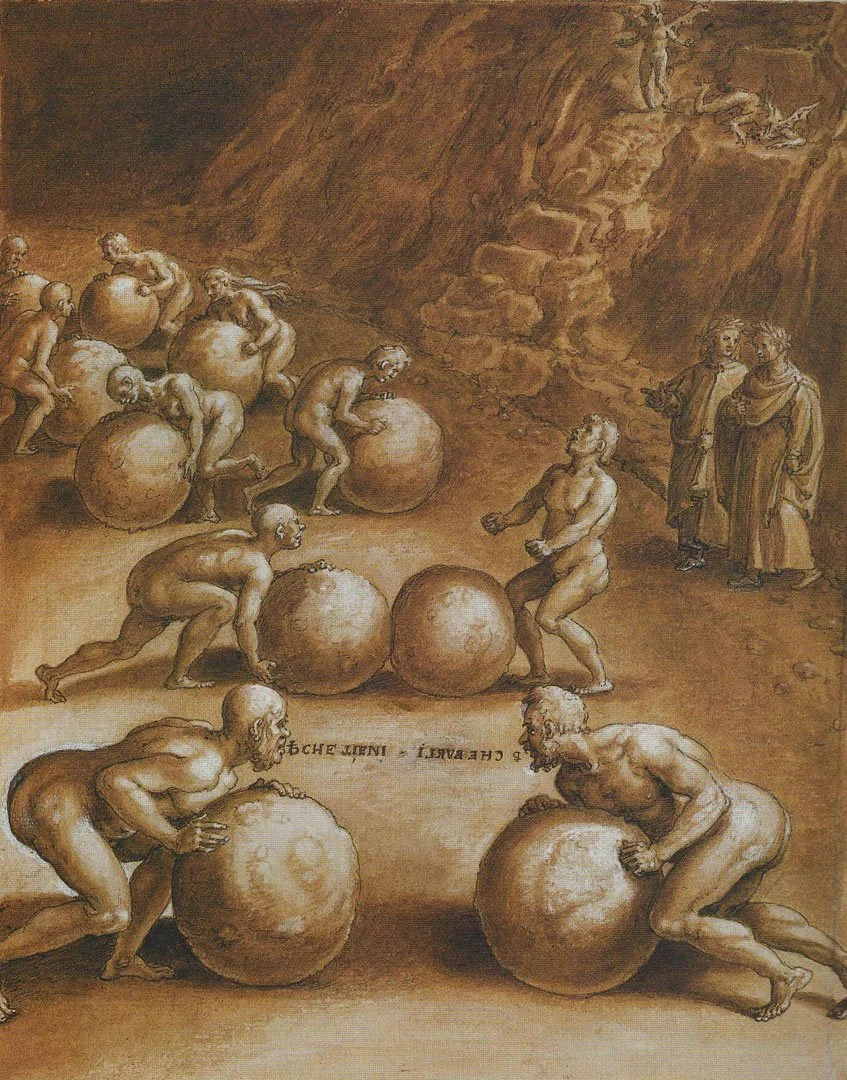

Giovanni Stradano’s illustration of the avaricious and the prodigal in INFERNO, Canto VII

We finally get a glimpse at the hoarders and the wasters, the avaricious and the prodigal. They're mostly clergy, from run-of-the-mill clerics all the way up to popes.

And we come to the first overtly anti-clerical passage of COMEDY.

Perhaps more importantly, INFERNO, Canto VII shows the stress the poem is increasingly under.

It also shows that the poetic structure and voice need to change for the poet to find the right mix to write what will become the greatest work of Western literature.

Consider supporting this work with a small monthly stipend or a one-time donation:

The segments for this episode of WALKING WITH DANTE:

[01:15] My English translation of INFERNO, Canto VII, lines 36 - 66. To read along, find a deeper study guide, or continue a conversation with me about this episode, scroll down this page.

[03:15] The pilgrim feels pity, but perfunctory pity perhaps, as the clergy roll their rocks.

[09:30] Three points on the anti-clerical passages in COMEDY and in this canto in particular.

[12:30] Why does the pilgrim not recognize those pushing the rocks? I've got several answers you can pick among.

[18:23] The golden mean, Aristotle's vision for ethics: It's taking over. Should it?

[22:47] An extra-Biblical character: the goddess Fortune. Although we had an orthodox character in the last passage (Michael, the archangel), why this turn away from orthodoxy?

[26:28] My confession: I'm a structuralist. I think a look at structure here can help us see some of the problems the poet has to solve to get COMEDY written.

My English translation of INFERNO, Canto VII, Lines 36 - 66:

And I, feeling as if my heart had been run through, said,

“My master, please fill me in

On who these people are. And were these all clerics,

The tontured ones on our left?”

And he to me, “All here were so cross-eyed

In their minds back in their original lives

That no control governed their spending.

“They bellow out this stuff clearly

When they come to the two points of the circle

Where their contrary guilt divides them.

“These were clerics, who have no hairy caps

On their heads—and popes, even cardinals,

In whom avarice reached its highest achievement.”

And I, “Master, among these last sorts

I ought to clearly recognize some

Who were fouled with this sin.”

And he to me, “You’re collecting empty thoughts!

The lack of discernment that besmirched their lives

Has darkened their souls beyond recognition.

“They will come to their two collisions for eternity;

These will be resurrected from their tombs

With clenched fists—and these will rise with short hair.

“Inappropriately tossing stuff out and storing it up have taken all of them

Out of the beautiful world and set them to this scrapping—

I can’t offer a nicer word for it.

“Now you see, son, what buffonery

Comes to these because of Fortune’s goods,

So much so that humans fight each other over them.

“All the gold that’s below the moon,

Or ever could be, is not enough

To give rest to one of these worn-out souls.”

FOR MORE STUDY

A clarification:

I made a confession to being a structuralist in the episode. Let me delve further into that stance. I was trained to see texts as archeological artifacts. If you and I came on a text—let’s say Virginia Woolf’s MRS. DALLOWAY—what would that novel tell us about the historical moment, its relationship to World War I, the notion of the self, the ways the self can be presented, what this literary form is supposed to do? Part of how I was then trained to look at that historical artifact is to examine it as a piece of architecture. How does it (try to) hold together? (For DALLOWAY, through a miasma narrator who can move in and out of characters’ minds, with varying success.) What’s its foundation? (For DALLOWAY, stream of human consciousness paired uneasily with the growing notion of a woman’s unique, even privileged perspective). What compromises must it make to stay erect? (For DALLOWAY, it must grant the nasty likes of Peter Walsh a decent and even redemptive point of view, since everyone is caught in the matrix of consciousness together). And what are the things that can undermine its structure? (For DALLOWAY, Woolf’s pernicious antisemitism and her inability to fully envision Clarissa Dalloway because of her own ambivalence about a powerful woman.) I intend to bring that same energy to Dante, although 1) his poetry is further back in time and so it’s an admittedly murkier glimpse into what the work is trying to do (and what it’s not succeeding at doing), 2) the architecture of COMEDY changes over its course because the poem’s thematics change (simply put, from a search for justice eventually to a search for peace); and 3) the notion of character and plot are very different for an author in Dante’s day, partly inaccessible to us.

Four translation issues:

There’s definitely a defect in the clerics’ vision. But what? Here’s Virgil’s explanation of them at lines 40 - 41: “Tutti quanti fuor guerci/ sì de la mente in la vita primaia” (literally, “All each was [???],/ so of the mind in the life first”). “Guerci” is the problem. I translated it as “cross-eyed,” in a bow to Robert Durling’s understanding. John Hollander prefers “squinty.” Stanley Lombardo likes “unbalanced.” It has more to do with sight, most likely, as if the mind needs glasses to see properly. This metaphoric understanding of their plight may tie back to the notion of envy, which may lie under greed and overspending. In the Florentine, the word “envy” comes from the verb “invidere,” or “in-videre”—that is, “to not see.”

Virgil goes on to diagnose the problem with this group: “che con misura nullo spendio ferci” (literally, “who with measure none spending governed”—line 42). It is the phrase “con misura” that brings Aristotle (via Aquinas) into the argument: the notion that there can be some sort of measured response to life as a whole, not hoarding all you’ve got or spending it like mad. We’re probably meant to see that lack of a “misura” (“measure”) as the problem . . . but what measure can there be in an age bent on building incredibly ornate Gothic cathedrals and lavish palaces?

I translated line 59 as to say that they’ve lost“the beautiful world,” abandoned by their overspending and hoarding; but the Florentine is more sensual: “lo mondo pulcro” (line 58). It carries a notion of even sexual pleasure, something that should certainly be foreign to the clergy. Perhaps that’s the jibe. But it’s a curious one: “pulcro.” Maybe avarice and prodigality, both designed to give the world more “pulchritude,” end up turning it barren.

Note the rhyme sequence with “zuffa” (or “scrapping” as I translated it—line 58). It rhymes with “buffa” (“clowning around”—line 60) and “si rabuffa” (“tangle themselves in”—line 62). It’s almost comic. It even sounds so! Think back to what I claimed were comic rhyming sequences about Plutus at the start of the canto. This whole thing has a slapstick quality about it, something no member of the clergy would appreciate.

Four interpretive issues:

Just to make it incredibly clear, I find that there are two “outside” influences brought into the theology of this passage: Aristotle’s ethics and the goddess Fortune. Neither is particularly Christian, although both become part of Christian theology, the former via Saint Thomas Aquinas (and many others) and the latter by Boethius, a highly regarded, early philosopher-theologian. Perhaps I’m being too Protestant here, demanding too much “sola scriptura”; but I think these outside influences, common though they be in Dante’s day, bring their idiosyncratic arguments and even metaphoric imaginings into Christian discourse, causing rifts and cracks to open up in the orthodoxy Dante (and others) would like to espouse. Right now, they’re happening in the poem in a jumbled fashion. Or to put it the way I did in the episode, the poet is reaching here and there to help him understand his world-building journey. He will have to learn better balancing skills. Not that he won’t need Aristotle and Boethius ahead. But he will have to begin to trust his skill to build a world that explains itself, that finds its first point of reference in itself. That’s the task of any great artist.

I spoke about the anonymity of the damned in this circle of hell. No one steps forward to be known. I offered several reasons for that, but here’s another: Is there a way that avarice and overspending erase the self? In the end, does the accumulation or rabid dispensing of wealth, alleged to separate you from the herd, actually cause you to disappear? Yes, the wealthy are notoriously private, fearful that they be hounded for money. But even in their privacy, is there a way that their insularity causes a (slow?) erasure of who they are?

At lines 46 - 48, it seems as if the spenders are the run-of-the-mill clergy, whereas the hoarders are cardinals and popes. Is there a rationale for that division? In Dante’s day, almost all of upper echelons of the church would have come from the gentry: landed, royal, or otherwise wealthy. The vicar of a local church is much more likely to be commoner, someone’s son who actually landed a nicer perch than, say, the family farm. Does this rationale work in some way? Or perhaps popes and such don’t have anything to buy. If they want anything, the church buys it for them. So they’re free to hoard their personal gold, even their family funds.

Although it’s not crucial to this passage, don’t miss the reference to the moon at line 64 - 65: “tutto l’oro ch’è sotto la luna/ e che già fu” (literally, “all the old that is underneath the moon/ and that already was”). What’s happening here is “sublunary.” That will become important to what Virgil has up his sleeve next.

One journaling prompt:

No matter your financial situation, how can money be a curse? What does the accumulation of wealth do to an individual? The vast majority of lottery winners lose their fortunes within a decade, even a few years. Trust funds can be blessings . . . but are often curses. What’s at stake here? How can a lot of money damn you in the long run?