26. Damning Lust, Then Confusing It With Love: INFERNO, Canto V, Lines 52 - 87

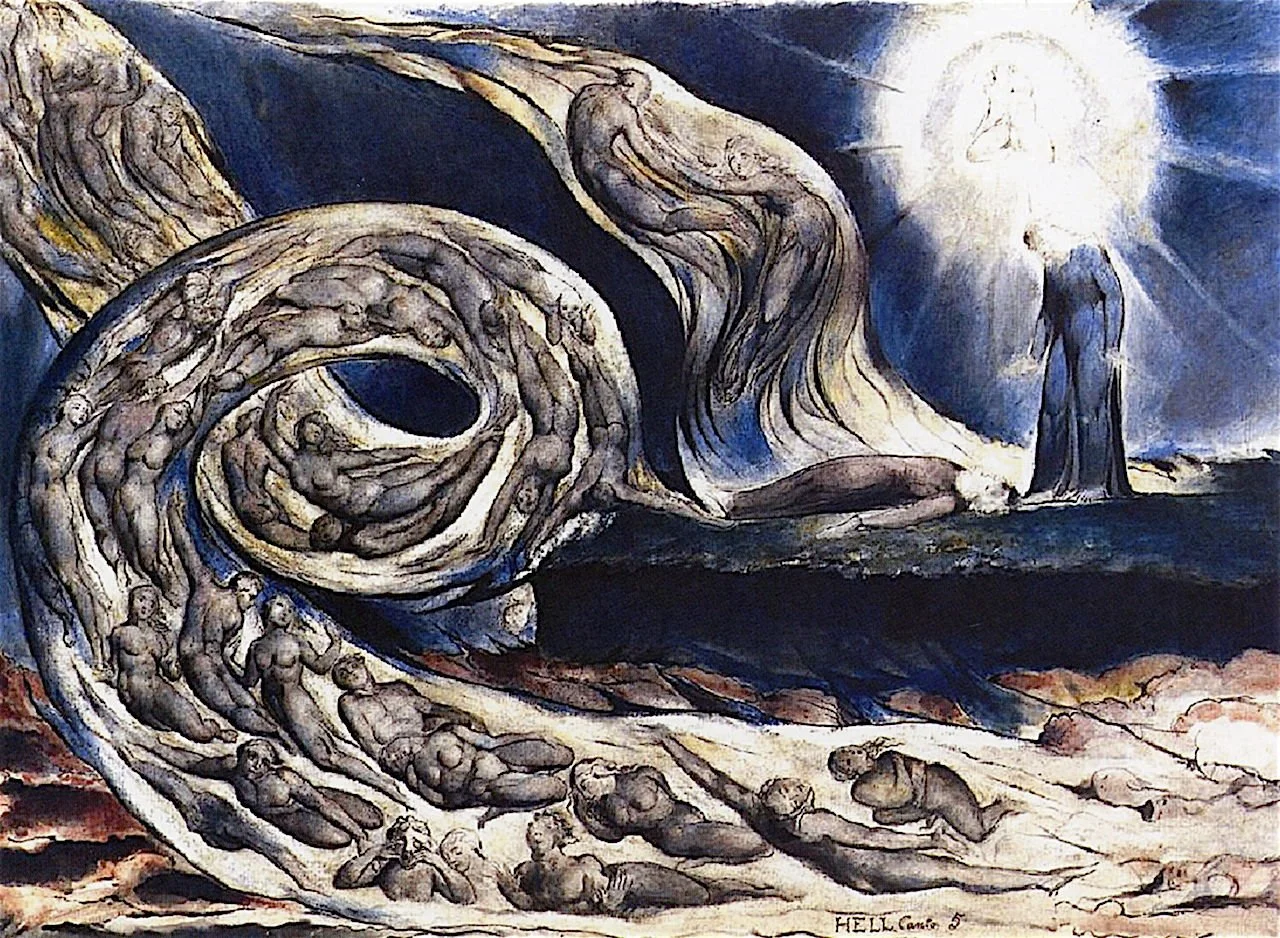

William Blake’s incredible swirl of the lustful on the wind.

The pilgrim, Dante, has just asked his guide who is tossed in lust's whirlwind.

Virgil answers with a list of the "greats" out on the wind: figures from antiquity, the Trojan War, and even medieval romance.

In so doing, Virgil redefines lust away from “reason subjugated to the appetities” and to something much more socially disruptive.

Then both Virgil and our pilgrim (plus maybe our poet in the background) make a further redefinition and perhaps a telling mistake: They confuse love and lust.

Consider supporting this work with a one-time donation or a small monthly stipend:

The segments for this episode of WALKING WITH DANTE:

[01:43] My English translation of INFERNO, Canto V, lines 52 - 87. If you'd like to see my translation, find a deeper study guide, or continue the conversation with me by dropping a comment about this episode, scroll down this page.

[06:24] The structure of Virgil's catalogue of historical figures on the wind.

[07:10] Picking out those on the wind and the "novelle" about them: four women, three men; three involved with incest, four with civic unrest. Plus, the shocking movement from an orthodox definition of lust to the invocation of love, the greatest Christian virtue.

[27:41] The pilgrim's request: Can I talk to the two who are so light on the wind?

[29:48] Irony invades the passage. It tints its rhetorical structure and even invades the simile: doves, a traditional symbol for the third person of the Trinity.

My English translation of INFERNO, Canto V, Lines 52 - 87:

“The first of those whose stories

You want to know,” he then told me,

“Was empress of a polyglot world.

“She got so rotted by the vice of lechery

That she made lust legit in her laws

To blot out the shame she’d brought on herself.

“She is Semiramis—we read that

As his wife, she succeeded Ninos [to the throne]

And held the land that the Sultan now rules.

“Next is she who offed herself for love

And ripped up her faithfulness to the ashes of Sychaeus.

And then there’s raunchy Cleopatra.

“Look at Helen, around whom so many horrid times

Revolved, and look at the great Achilles

Who waged a final battle with love.

“Look at Paris, Tristan!” And he pointed out

More than a thousand shadows and named them, too,

Every one whom love had cut off from our life.

After I heard my teacher name

The ladies of old and their knights,

Pity grabbed me, and I was almost lost.

I began: “Poet, I really want

To speak with those two who go together

And seem so light in the wind.”

And he to me, “You will see them when they

Get closer to us. Then beg them

By the love that drives them and they will come to you.”

Right when the wind bent them close to us,

I spoke up, “O worn-out souls,

Come talk to us, if no one disallows it.”

As doves are drawn to their sweet nest

With their wings open and firm, summoned by their desire,

Moving on the air, wanting to land,

Just so these spirits slipped away from the flock near Dido

And came to us through the malevolent air—

That’s how strong my endearing cry was.

FOR MORE STUDY

Four translation issues:

There’s one rhyming pair that’s impossible to render in English. When Virgil speaks of Semiramis, he says she made her libido licit “in sua legge” (“in her laws”—line 56). Two lines later, he says we could even read about her and her successor: “di cui si legge” (“of whom can be read”—line 58). The poet has rhymed “legge” with “legge,” “law” with “reading,” a repeated word with two meanings. Dante may well be making a complex point about interpretation, about the ways that reading creates legality, about how legality creates what can be read (or written and therefore read), or even about how laws and reading are interconnected into civic, interpretive acts. All fantastic stuff . . . but as I say, impossible to see in English.

If you want to see the four times where love (or a form of the word) comes up in the text, check out lines 61, 66, 69, and 78. To compound matters, “desire” comes up at line 82. It’s important to remember that all these instances of “love” follow the original statement about “libido” (the illicit lust) of Semiramis at line 56. There may have been a quiet shift in the passage.

Because I made much of it in the episode, we might as well look at the text at lines 74 - 75: “ . . . que’ due che ‘insieme vanno,/ e paion sì al vento esser leggieri” (literally, “ . . . these two who come together/ and seem so on the wind to be light”). First off, notice the hard, inelegant percussion of “que’ due che” (“kway doo-ay kay”). Perhaps we should be on our guard for whatever comes next, particularly that difficult word, “light.” Are these two lovers “light” as in they rise above their circumstances, almost Stoic? (That won’t be the case for one of the pair ahead.) Or are they “light” as in “not very important”—that is, “lightweight”? One way to solve this may be to look at the rhyming words, often a poetic clue for what Dante intends. He rhymes “leggieri” (“light”) with “voluntieri” (“I would want”—a courteous way to begin his speech at line 73) and “cavalieri” (“knights—at line 73). Whatever else we can say, the “light” ends a rhyme trio that’s courteous and chivalrous. (Keep this in mind when we hear their story ahead.)

While we’re on the question of rhymes, there’s an ugly set in the passage: “priega” (“entreat”—line 77), “piega” (“bends”—line 79), and “niega” (“forbidden”—line 81). You may be able to sound out these words in the Florentine and hear them clang against each other. Notice, too, that they move from Virgil’s speech, through the poet’s space, and into the pilgrim’s speech. The poet may be signaling something from the background. What?

Five interpretive issues:

Although I made reference to the Holy Spirit (the third person of the Christian Trinity) with the simile about the doves, there may be another link to that Christian entity in this passage. At line 54, Semiramis is said to have ruled over “molte favelle” (“many tongues”). When the apostles were filled with Holy Spirit at Pentecost, tongues of fire fell on them, accompanied by a loud, yep, wind. The apostles then spoke in “many tongues.” There may be a way that one of the pair coming down on the wind to speak to our pilgrim is an infernal inversion of the Holy Spirit, who is known to have descended and having inspired speech (as well as even writing—that is, the Bible).

If we take Virgil’s answer to how to get the two on the wind to come near them (lines 77 - 78) and pair it with our pilgrim’s pride at getting them to respond because of his “affettüoso grido” (“affection-filled cry”—line 87), we can pose a legitimate question to our old Roman poet: Are you tempting the pilgrim, Virgil? Or testing him? Or worse, leading him astray? We already know that Dante is on edge, in fact almost “lost” (line 72). Yet Virgil still identifies the winds around them as those, not of lust, but of love (“quello amor che i mena”—or “this love that moves them”—line 78). Virgil certainly doesn’t warn the precarious pilgrim. Instead, we might say that Virgil pushes our pilgrim further into the hairline fracture between lust and love. Which brings up the bigger question: What is Virgil up to in this passage?

As to the (trinitarian) trio of passages about doves in COMEDY, they are 1) the wind-blown lustful pair here (INFERNO, Canto V, lines 82 - 84); 2) the quietly feeding flock of doves on the shores of Purgatory (PURGATORIO, Canto II, lines 124 - 129); and 3) the great apostles Peter and James who come down as doves from the Holy Spirit (PARADISO, Canto XXV, lines 119 - 121).

I make a lot about the muddling of lust and love in this passage. But is the division as clear as I want it to be? Might there be a way that lust is truly an expression of love? My separation of the two may be too hard-edged, even too Calvinist for Dante. What if we take these lines at face value? What if Achilles did indeed feel love, even though it was for a woman from the other side of the war? What if love is really to blame for those who depart “from our life” (line 69)?

If Virgil points out “più di mille” (“more than a thousand”) shades who’ve been done in by love/lust (line 67), how long are Dante and Virgil standing at the edge of that ruin and looking into the winds? And since we’re tallying things up, Virgil first names seven of the damned; then a pair show up. So that’s nine in total. Nine is the number Dante frequently associates with Beatrice. In the VITA NUOVA, he meets her when he’s nine. And nine is three squared, a Trinitarian reference. The irony here may be more complex than we first imagine.

One journaling prompt:

Since we’re sitting at this hairline fracture in the text, how can you tell the difference between lust and love? Or is there a difference? Or should there be a difference? In a world of hook-up websites, there is no difference. But should there be? Or is this crack a temporary one: one should see a difference between the two at certain points of life and not at others?